So here we are, rolling up to 2022 and approaching our second year of being fully remote in a pandemic. We’ve all found new ways to execute on our deliverables and meet our deadlines in this new remote world, but gone are the days of running into a smiling familiar face in the office, casually grabbing a snack or coffee with a teammate, or gathering a posse to go to lunch. That leaves a missing piece and an unanswered question that resonates with many of my colleagues: How do we build team culture?

Team culture is something that can easily be taken for granted, as it can often flourish organically simply by showing up. However, when team culture goes missing, so does compassion and empathy for teammates. Social cues that a team member could use some help, feedback, a pat on the back, or a day off get lost over compartmentalized video chats. This can be specifically challenging for designers and creatives who live in a world of constant criticism of their work, thrive on inspiring one another, and benefit from tapping each other on the shoulder for a gut reaction or an impromptu brainstorm session.

Gone are the days of running into a smiling familiar face in the office.

A true robot of an employee might be asking: Why does this matter? The team is delivering against goals and our success metrics are going up and to the right! We do a much better job achieving those business goals when our teams are happy, collaborative, open to feedback, trusting, and invested in seeing each other succeed. We’ll wake up jazzed to do our jobs and won’t be spending the majority of our time hiring against turnover and ramping up new people. Connection makes work feel less like work and more like something we genuinely want to do.

Forging the remote-first path

Before providing more insight on the experiments we’ve tried on my teams, I want to provide a little context on myself. We’re talking about culture and empathy here, so it is only fair that I build a little rapport with my readers. I’ve been leading design teams at Square for more than five years and spent my first two years in the San Francisco office before moving to Milwaukee and going fully remote. I moved about a year before the pandemic, when very few designers, and even fewer design managers, were remote. I had to quickly learn how to adapt to my new working environment. How was I going to stay on top of my design team’s work? How were design reviews and brainstorms going to work if we aren’t all in the same room pointing at the wall or screen? How was I going to interview people? You know, all of the things the business really cares about to ensure we are releasing the world-class experiences our customers depend on us for. Solving these tactical problems wasn’t as challenging as I thought it would be, since they were necessary process adjustments. But the problem that consistently eluded me was how to build a healthy, fun, empathetic, and inclusive team culture when I wasn’t in the room to crack jokes, take people to lunch, and have normal day-to-day conversations that didn’t feel forced as the bookends of video meetings and 1:1s.

When I first went remote, I was definitely the odd man out. Everyone was typically in a meeting room together in the office while I was always the guy on the screen. I was missing out on whatever was happening before and after those meetings that everyone else was able to experience. To solve this, I took a brute force approach of flying to either San Francisco or New York once a month to build rapport with my colleagues and humanize the face on the screen who was responsible for criticizing their work.

Creating culture on Hangouts, in Figma, and beyond

Enter the pandemic, the great equalizer (for better or worse). All of a sudden, everyone was on the screen. It was no longer an option for me to fly out and see people. The problem had expanded beyond my personal perception and rapport with the team; it was now my entire team’s problem and team culture was at risk. On top of that, many team members were single, living alone, or unable to see their friends and family. Their primary social interactions were with their coworkers, and, in some cases, all they had to do was work. This was the point where I realized we needed each other more than ever, and we needed to really focus on tackling the problem of establishing remote team culture. So how can some of that organic camaraderie exist without adopting a process of forced fun?

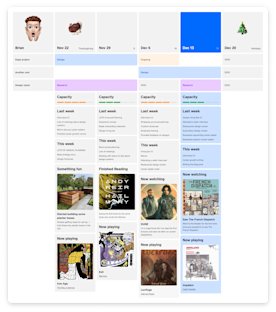

Example of our design weekly file

We started by making some adjustments to our weekly design team kickoff meeting. This meeting used to be very much geared around status check-ins for the work, with a lighter emphasis on people. We flipped the purpose to be more about getting to know each other and shifted the emphasis on work updates to be asynchronous. As designers, we leveraged the tools that we knew best to improve our processes. We created a template in Figma for everyone to share what they worked on the previous week, what they are doing the current week, their perceived capacity, what they have been listening to, what they are watching, any fun things they did over the weekend, etc. We spend the first five minutes of the meeting commenting on the file and sparking conversations.

Examples of fun things people share in design weekly

The next 10 minutes is focused around any discussion topics I have for the group or topics others want to raise. It is important to provide this time so anyone can share something that is on their mind. We reserve the last 15 minutes for a member of the team to do a presentation either about their life, a cool vacation, a Cribs-style walkthrough of their house, or something that inspires them. I was shocked at how well-received these presentations have been and how much we all got to know each other better. We have learned about lots of interesting hobbies (like speed cubing, pottery, painting, music), wildly different upbringings (being raised on farms, moving a lot as an army kid, and celebrity family friends), and, in some cases, deep personal challenges.

An example of the types of personal experiences I have shared with the team

Work-free zones

On top of our weekly meeting, we put together a formalized timeline to ensure we were spending time together apart from work. Once a quarter, we informally have a game night, trivia, or something else low-lift that doesn’t require much planning. Some examples of fun things we have done for these have been this awesome Escape the Room in Figma, Jackbox Games, playing Among Us, and going bodyboarding at the beach.

We also do an annual formal “offsite” where we carve out a larger time frame from our workday and do something more involved. Some examples here are coordinated team lunches where we send everyone a meal, take classes together like cooking or tie dye, or things like Airbnb Experiences.

Our new annual tradition of Figma white elephant

Lastly, we do ad hoc events for things like holidays, birthdays, and new-hire welcomes. A particularly fun example of this is our white elephant party, which we conducted in Figma. Everyone picked out a gift, wrapped it (hid an image under some wrapping paper), and when it came time to choose a gift, people would move it to their designated gift area and open it (turn off the wrapping paper layer). After many cutthroat gift steals, the gifts landed with their final owners and the givers purchased them and shipped them directly to the recipients. This was honestly more fun than doing white elephant in person and we intend to carry on this tradition every year.

The things that make you a successul remote leader are just the things that make you a good leader.

All in all, nothing truly replaces organically getting to know each other in person, and we are all looking forward to the day when we can get together again. However, in many ways this remote world has made us think bigger and be more inclusive. We’ve broadened our circle and created processes to get to know more people at scale. When the pandemic started, I had a lot of people reaching out to me asking for advice on how to navigate leadership in a remote environment. Ultimately, what I arrived at is that the things that make a successful remote leader are just the things that make you a good leader: establishing processes that endorse transparency, promoting asynchronous collaboration, and creating environments where people feel comfortable and rely on each other. Even if we all end up back in an office together some day, the processes established from this grand experiment will certainly live on, and how we work has changed for the better.