For this installment of Creator Series, we spoke with Bay Area filmmaker Mohammad Gorjestani, director of several films in Square’s For Every Dream series, including Yassin Falafel, Made in Iowa, Lakota in America, Sister Hearts, and Exit 12: Moved by War. Together, these films form a stark, moving revelation of what it means to be an entrepreneur in the context of America amidst adversity.

In this series, we chat with some of our world-class creative partners and collaborators from over the years. Here, Mohammad Gorjestani and Global Brand Group Creative Director Eileen Tjan talk about the long road that led Gorjestani to filmmaking — and how each step would inform an artistic mission to empower those he works with on both sides of the lens.

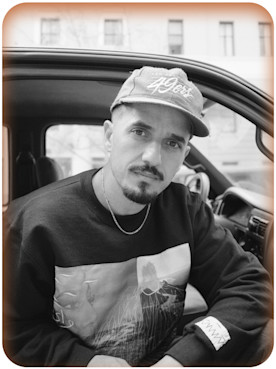

Mohammad, thank you for joining us. Mind introducing yourself? How would you describe yourself?

I describe myself as a visual storyteller and artist who prefers to work in the medium of film, at least for now. I also do other things: photography, creative direction. I’m also a partner and founder of EVEN/ODD, a creative studio and production company.

Let’s see… What else would my mom want people to know? I was born in Iran post-revolution. My parents tried to stay in Iran as working-class artists, something that you could do in Iran. But due to the Iran-Iraq war — and specifically airstrikes in Tehran, where we lived — we had to flee. Our first stop was Turkey, where we lived in a ten-by-ten room for a year while my dad made many trips to the nearest U.S. embassy in Dubai to try to get our visas granted, and eventually, they were and we were assigned to San Jose, California.

I grew up in West San Jose in a Section 8 immigrant melting pot community against the backdrop of Silicon Valley. This was the environment that really shaped my attitude towards the world and my understanding of America at large.

Is there a story you can recall from childhood that you loved? One that made you want to tell stories yourself?

This might sound a little corny or low brow, but the truth is the truth! I think when I think of my childhood and things that really caught my hard-to-grab attention, Goosebumps is what got me interested in the concept of plots and stories, or at least thinking about how to write my own. My third-grade teacher gave me a copy because I guess I told her I wanted to read scary stories instead of the “boring” books we were assigned. I remember just getting lost into the page and feeling a bit transported.

I think what captured me about those books looking back, though, was that the stories often took place in suburban Americana areas, which were a stone’s throw away from me growing up but felt unattainable from within the confines of the apartments and class I grew up in. They were just places I walked by, and these books kinda placed me in that reality.

But to make a connection to filmmaking, I think I have to mention To Kill a Mockingbird. I read the book freshman year of high school and I thought it was fine, but the movie really captured me. That was the thing that started to actually make me curious about how written text was interpreted visually. Every time we would read a book, I’d be so excited to watch the movie. I became pretty fixated on comparing the book to the film, trying to critically analyze why some of the decisions were made when adapting the book to the screen.

Did that compel you to start telling stories as well?

What really made me want to explore the actual craft of filmmaking was when I first watched Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry. I watched this film shortly after I had to stay back while my parents took a trip to Iran when I was 18. I was pursuing a wrestling scholarship and needed to stay home and train. I began to realize that I had a lot of homesickness I hadn’t really recognized, and this film kinda cured that. It just transported me to a place I was very familiar with because I spent the first five years of my life in Iran. I remember stepping away and being like, “What was that experience? Why am I still thinking about this? How did they make that?”

That was the first film that really made me start to imagine narrative and the idea of placing images and plot points in a sequence to make a larger statement or create a feeling. You don’t really think about creativity being a profession when you grow up in a certain class. If anything, I saw my parents, artists in their life in Iran, come to the United States and stop being artists because that’s what they needed to do to survive.

Footage from Lakota in America

What motivated you then to tap into your creativity?

I’ve thought about this a lot and I think the truth is that my parents are extraordinary artists, so I think the uneventful but real answer is that it was in my genes. It was just a force of nature inside of me that had nothing to do. It was almost like at some point I had to just give in to it.

I think with most first-generation kids and kids of diaspora — you spend so much of your time watching your parents survive. You’re seeing how they’re trying to assimilate and you assimilate. But then you start to actually go back to your culture, to examine yourself and your relationship to your nationality, history, and the events that caused your immigration. It’s like casting a searchlight inside yourself, and then you see things that you want to go explore more and understand. That is where I started to find the clay that I began to shape and mold until it formed something I could grasp onto as an idea took a shape — and I kept pursuing it from there.

When did that all start to turn into filmmaking?

I had just left to go to college to start summer practices for the wrestling team, and a few months in I got hurt. I tore my rotator cuff, and it was like my fourth injury that year. My time had come, and I think I kinda grieved that. I just kinda sat on the couch, really depressed, watching a lot of movies: City of God, Seven, Blow — that very specific moment in cinema. Then I started going to junior college and took a couple of film classes because, honestly, I heard they were easy and I liked watching films. I was like, “I'm down to hang out in a dark room, watch movies, smoke a joint before class, and see how it goes.” There I was introduced to actual Cinema in a way that was formal. It was like, “Wow, there’s a science to this, and a practice.” I think I got hooked but didn’t quite know it.

One of our assignments was to write a story outline, and I submitted mine thinking it was not that great, but my teacher was like, “This is really good. You should do something with this. Have you thought about film school?” Mind you I’m also working at a golf course and also washing dishes when I’m not at class, so I was like, “What the hell is ‘film school’? I don’t know anybody that goes to film school.”

She helped me look into it, and I realized that places like USC or NYU were outside of the economic reality that I could muster up, so I ended up at a one-year program in Vancouver that I could afford on a student loan and a bunch of money I’d saved up working through high school. I made my first film through this program, a very personal film.

During my time in Vancouver, I was shedding a lot of baggage because I no longer had to be defined by where I was from, and in some ways that allowed me to dig back into who I was beyond expectations. What was left was a lot of vulnerability, and that took me back to realizing how much immigration and growing up where I did had an impact on me. It was the first time I’d begun to unpack myself in many ways. I just wrote a story, almost subconsciously, then made it a screenplay, then I ended up making it and it got into the Tribeca Film Festival.

I was the youngest filmmaker at this festival — this is in 2006 — and I’d never been to New York, but it was the first time that something I made was recognized in a way that made me feel like this was something I could do. And it was the first time I felt that tapping into very personal feelings had a tangible reward, and that was important for me in gaining the confidence to break free from the formula the society wanted me to follow based on my socioeconomic background and my own perception of what kind of person I should be.

But of course it’s way harder than that. I moved to San Francisco that same year and spent years working in restaurants, trying to scrounge my money and time to work on my own ideas and write grants. And I made a lot of really terrible things, a lot of work that had little focus, but the credit I give myself is that I just kept making and playing.

So much of being an artist is about shedding bad work. This is something that people don’t want to admit, but I really believe it’s a natural part of creative development.

I look at those years as a time of learning how not to do things.

But in filmmaking, especially as a director, this idea that your job is solely to be an artist is pretty bogus to me; it’s as much a leadership role as it is a creative role. Filmmaking is so collaborative. Your main job as director is to get the most out of the people around you, to guide them and help them achieve their potential, to drive the project through all of the gauntlets that projects go through and steer all these things towards a singular direction.

How do you stay inspired in your practice? How do you bring your creativity to all of these different types of work?

I have a lot of rituals and habits. It’s almost like creative practice: “Okay, now it’s time to watch a film; now it’s time to revisit a film; now it’s time to pick a photographer and study their work.” A lot of my creative ideas come when I go running, because for me that’s my most meditative state where everything else around me falls away. You need routines that help you unplug from responsibilities and expectations and allow you to tap into the world creatively. These are like wells of rejuvenation and inspiration.

People also ask me a fair amount how to break into commercial or brand work, and my response is always the same: focus on your personal work and make it. For me, it’s just about maintaining a strong conviction in the things that are important and then adapting that to the opportunities that come my way or opportunities I generate myself. I’ve yet to be failed by investing in myself and my own personal work, so it’s hard for me not to recommend that to everyone else. I think the trick there, though, is to be okay with that being a long journey with lots of ups and downs. Most people don’t want to deal with the downs, and in creative work those downs are very hard to deal with, but you have to learn how to deal with them. If you can, you will be rewarded eventually.

What’s important to you in taking on work? What compelled you to take on the For Every Dream film series, the project you worked on with us at Square?

Dreams was a fairly pivotal moment in my work and EVEN/ODD as a studio — and I think for Square as well. Again, it came out of personal work. My work has always been at the intersection of class, culture, immigration — basically all the things that informed who I am and how I grew up. What led to Dreams was we’d made a series called The Boombox Collection that was a visual document of working-class hip-hop artists who’d inspired me when I was younger. I was curious about their lives as older musicians and I think the undertone of it felt like a bit of an entrepreneurial story of creative survival. I made the film with Boots Riley, with Zion I, rest in peace. [Then Square Global Head of Creative] Justin Lomax, who in his own right is a Bay Area rap culture legend, saw those films.

I quickly realized two important things about Justin and [Group Creative Director] Sean [Conroy] and the larger creative team: they really cared about things that mattered and aligned with what matters to me and EVEN/ODD; and they also really believed in the company they worked at, but more than that, they believed in the people they had met who use Square products. This was an important detail — this just wasn’t their job, this was something they valued as individuals. And the way they talked about these business owners, I believed them. And as we peeled the layers back, it was evident that that community was ripe for storytelling.

I think this was the foundation of the films maintaining their integrity, because Justin and Sean advocated for the things that mattered, and to the company’s credit, we held the line more than any branded project I had ever been a part of. It’s easy to tout the films’ success after the fact, but when you are in the trenches making decisions as the world is happening in real time, it’s not as easy. There were many, many ways these films could have ended up bad, but they didn’t because people in charge wouldn’t allow it.

I think for these films to be created during the Trump years, amidst America’s unveiling, allowed there to be a platform for the films to stand on. They were a bit of a counterpunch to the narratives that were beginning to rear their ugly head in culture and discourse. But still looking back, it was a bold project, given that it was one of the first campaigns that took a direct stand and didn’t really pander to the dominant society.

Footage from Yassin Falafel

But also how the films were made was very refreshing, especially in the context of advertising. They were empowered to be made as films, and I was given the space to work as a filmmaker — this credit really belongs to Square. I think the hallmark of the Dreams series reflects this, because I think it delivered as a campaign on Square’s purpose of championing entrepreneurship, but also the series did well critically in the film community and in culture. Exit 12 was the first branded film that won an Oscar-qualifying film festival (SXSW) and was acquired by a major studio in Fox Searchlight.

All these seemingly different films — from a story of a Syrian refugee to one of a factory town in Iowa — come together to start investigating this concept of the American dream and this system that we live in, how it works and who it serves.

These economically challenging situations represent much more than just people’s bank account; they represent their livelihood, the places they love, their culture.

Given the emotional rawness of the films, did you face any challenges with these projects? Did anything ever get overwhelming?

One thing I do spend time accounting for before a shoot is the mental side of production, making sure I am preparing to step into the project focused on execution and nothing else. Part of this requires you to flip on and off a switch that helps you compartmentalize some of the emotions that go along with difficult subject matter. In terms of dealing with the subject matter at hand, I just don’t allow myself to get emotional, because that will deter me from doing the job I need to do. I just try to flow with the energy I’m shooting. All I’m thinking of is delivering what we need to make the edit work. When you are engrossed in that, you don’t really have time or mental space to be emotional.

And for me, I try to think about the subjects I work with as collaborators. You make them understand the value of what it is they’re doing, build relationships, and, from there, you can create trust. It’s pretty common for people to tell me they’ve revealed things about themselves they’d never shared with anyone. The flipside of that is where responsibility comes in, because part of the deal is doing right by them. And that pressure doesn't allow you to let your emotions get the best of you. You're just like, “I better f***ing do this right.”

How do you find the right collaborators?

I hate to reduce this down to a vibe, but it really is that. It’s pretty easy to figure out who you share a frequency with or whose frequency can contrast yours in a way that helps in collaboration. The non-negotiable is aligning in what the message of a project should be — especially in the context of advertising, since I’m dealing with real people spilling their guts for the benefit of somebody’s brand. I’m very aware of how powerful media is in shaping attitudes, so I take this work very seriously in that regard, and I’m not very flexible when it comes to message. Especially dealing with real people, you must do right by them and consider the project from their point of view. Are we going to show these people in the right way? Are we going to make them active participants in their story? The requestors — will they not simply pander to a dominant audience?

I'm not really interested in just making pretty images. I think we have a bit of an epidemic with this worship of what an image looks like rather than what it represents and how it was constructed.

In San Francisco, with all of these companies that have emerged in the last decade here, there’s a certain culture and progression. Companies first had to explain what they were making, and then eventually once that was clear, they had to start establishing who they are as a brand and what they stand for. It’s unique here because these companies were so technically led and built with an ethos that placed utility and functionality above everything else, which makes perfect sense in building products. UX and UI should be simple and delightful, but, to me, those principles don’t apply to art.

Art should be permitted to be messy, imperfect, emotional. Sometimes art’s minimal, but sometimes it’s excessive. Sometimes it’s beautiful, sometimes it’s intentionally ugly. It should make you uncomfortable, it should make you happy — all these things.

Footage from Sister Hearts

If there was one message you have for brands that are trying to tell these kinds of stories and relate more authentically with their audiences, what would that be?

If you’re only thinking about these things as data points, looking at things like diversity and inclusion and tagging it as “multicultural marketing” or something that just needs to be “accounted for,” you’re not spending the time to understand the real value of it. The real value is that the more people you put into the supply chain of a project that have life experience or stakes in what you’re doing, you’re going to get better, more specific work.

This era of post–George Floyd reckoning has been a bit bizarre to me in the context of content. Symbolic changes have been confused for structural changes, which is what is really needed. A lot of the initial energy to administer actual change has fizzled out. It feels like so much of the reaction was more crisis PR, companies frantically changing their perception to stay in business and relevant.

So now it’s even trickier to measure the integrity of partnerships and collaborations, but I think this again comes down to measuring who your partners are gonna be and who is motivating the stakeholders, looking at receipts and their history — are they suddenly turning a new leaf because culture has told them they need to in order to keep making money? But what we have gained in the last year is a larger set of language and lexicons to attribute to feelings that were often nebulous or micro in the way they chipped away at your spirit.

As creative people, especially minority creatives, we can’t allow ourselves to be gaslit by the system. We have to know that our experiences are valuable.

People need to stand next to us — we don’t need to stand next to them. We are building our own things, and we will continue to build our own things. We want partners who are interested in creating space rather than wanting to insert themselves to maintain their own social order. This will allow a shift in power to happen organically over time, which will deliver, eventually, real progress.

EVEN/ODD’s name actually comes out of this idea. As minorities or underrepresented people, we want more than just a month of recognition or that social good framing when it comes time to include us. By asking for this, it’s not really asking for a leg up or an advantage — it’s actually just about equal opportunity, or “even odds,” of access to economic mobility or cultural mobility or creative mobility. That’s why these things are important. It’s not just about checking a bunch of boxes — it’s about a redistribution of power and influence.